Atomic spectral line

In physics, one thinks of atomic spectral lines from two viewpoints.

- An emission line is formed when an electron makes a transition from a particular discrete energy level E2 of an atom, to a lower energy level E1, emitting a photon of a particular energy and wavelength. A spectrum of many such photons will show an emission spike at the wavelength associated with these photons.

- An absorption line is formed when an electron makes a transition from a lower, E1, to a higher discrete energy state, E2, with a photon being absorbed in the process. These absorbed photons generally come from background continuum radiation and a spectrum will show a drop in the continuum radiation at the wavelength associated with the absorbed photons.

The two states must be bound states in which the electron is bound to the atom, so the transition is sometimes referred to as a "bound–bound" transition, as opposed to a transition in which the electron is ejected out of the atom completely ("bound–free" transition) into a continuum state, leaving an ionized atom, and generating continuum radiation.

A photon with an energy equal to the difference E2 − E1 between the energy levels is released or absorbed in the process. The frequency ν at which the spectral line occurs is related to the photon energy by Bohr's frequency condition E2 - E1 = hν where h denotes Planck's constant.[1][2][3][4][5][6]

Contents |

Emission and absorption coefficients

An atomic spectral line refers to emission and absorption events in a gas in which  is the density of atoms in the upper energy state for the line, and

is the density of atoms in the upper energy state for the line, and  is the density of atoms in the lower energy state for the line.

is the density of atoms in the lower energy state for the line.

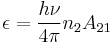

The emission of atomic line radiation at frequency ν may be described by an emission coefficient  with units of energy/time/volume/solid angle. ε dt dV dΩ is then the energy emitted by a volume element

with units of energy/time/volume/solid angle. ε dt dV dΩ is then the energy emitted by a volume element  in time

in time  into solid angle

into solid angle  . For atomic line radiation:

. For atomic line radiation:

where  is the Einstein coefficient for spontaneous emission, which is fixed by the intrinsic properties of the relevant atom for the two relevant energy levels.

is the Einstein coefficient for spontaneous emission, which is fixed by the intrinsic properties of the relevant atom for the two relevant energy levels.

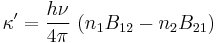

The absorption of atomic line radiation may be described by an absorption coefficient  with units of 1/length. The expression κ' dx gives the fraction of intensity absorbed for a light beam at frequency ν while traveling distance dx. The absorption coefficient is given by:

with units of 1/length. The expression κ' dx gives the fraction of intensity absorbed for a light beam at frequency ν while traveling distance dx. The absorption coefficient is given by:

where  and

and  are the Einstein coefficients for photo absorption and induced emission respectively. Like the coefficient

are the Einstein coefficients for photo absorption and induced emission respectively. Like the coefficient  , these are also fixed by the intrinsic properties of the relevant atom for the two relevant energy levels. For thermodynamics and for the application of Kirchhoff's law, it is necessary that the total absorption be expressed as the algebraic sum of two components, described respectively by

, these are also fixed by the intrinsic properties of the relevant atom for the two relevant energy levels. For thermodynamics and for the application of Kirchhoff's law, it is necessary that the total absorption be expressed as the algebraic sum of two components, described respectively by  and

and  , which may be regarded as positive and negative absorption, respectively the photo absorption and what is commonly called stimulated or induced emission.[7][8][9]

, which may be regarded as positive and negative absorption, respectively the photo absorption and what is commonly called stimulated or induced emission.[7][8][9]

The above equations have ignored the influence of the spectral line shape. To be accurate, the above equations need to be multiplied by the (normalized) spectral line shape, in which case the units will change to include a 1/Hz term.

The number densities  and

and  and the Einstein coefficients provide sufficient information to determine the absorption and emission rates, without further need for information about the physical state of the gas or about the local radiation field. Thus the above absorption and emission coefficients work for any state of the gas, so for equilibrium states and even for laser conditions.

and the Einstein coefficients provide sufficient information to determine the absorption and emission rates, without further need for information about the physical state of the gas or about the local radiation field. Thus the above absorption and emission coefficients work for any state of the gas, so for equilibrium states and even for laser conditions.

In contrast to the Einstein coefficients, the number densities, however, are not set simply by the intrinsic properties of the relevant atom.

Equilibrium conditions

The number densities  and

and  are set by the physical state of the gas in which the spectral line occurs, including the local spectral radiance (or, in some presentations, the local spectral radiant energy density). When that state is either one of strict thermodynamic equilibrium, or one of so-called 'local thermodynamic equilibrium'[10][11][12], then the distribution of atomic states of excitation (which includes

are set by the physical state of the gas in which the spectral line occurs, including the local spectral radiance (or, in some presentations, the local spectral radiant energy density). When that state is either one of strict thermodynamic equilibrium, or one of so-called 'local thermodynamic equilibrium'[10][11][12], then the distribution of atomic states of excitation (which includes  and

and  ) determines the rates of atomic emissions and absorptions to be such that Kirchhoff's law of equality of radiative absorptivity and emissivity holds. In strict thermodynamic equilibrium, the radiation field is said to be black-body radiation, and is described by Planck's law. For local thermodynamic equilibrium, the radiation field does not have be a black-body field, but the rate of interatomic collisions must vastly exceed the rates of absorption and emission of quanta of light, so that the interatomic collisions entirely dominate the distribution of states of atomic excitation.

) determines the rates of atomic emissions and absorptions to be such that Kirchhoff's law of equality of radiative absorptivity and emissivity holds. In strict thermodynamic equilibrium, the radiation field is said to be black-body radiation, and is described by Planck's law. For local thermodynamic equilibrium, the radiation field does not have be a black-body field, but the rate of interatomic collisions must vastly exceed the rates of absorption and emission of quanta of light, so that the interatomic collisions entirely dominate the distribution of states of atomic excitation.

In the cases of thermodynamic equilibrium and of local thermodynamic equilibrium, the number densities of the atoms, both excited and unexcited, may be calculated from the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution, but for other cases, (e.g. lasers) the calculation is more complicated.

Einstein coefficients

In 1916, Albert Einstein proposed that there are three processes occurring in the formation of an atomic spectral line. The three processes are referred to as spontaneous emission, stimulated emission and absorption and with each is associated an Einstein coefficient which is a measure of the probability of that particular process occurring. Einstein considered the case of isotropic radiation of frequency ν, and spectral radiance I(ν).[2][12]

Spontaneous emission

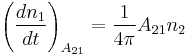

Spontaneous emission is the process by which an electron "spontaneously" (i.e. without any outside influence) decays from a higher energy level to a lower one. The process is described by the Einstein coefficient A21 (s−1) which gives the probability per unit time that an electron in state 2 with energy  will decay spontaneously to state 1 with energy

will decay spontaneously to state 1 with energy  , emitting a photon with an energy E2 − E1 = hν. Due to the energy-time uncertainty principle, the transition actually produces photons within a narrow range of frequencies called the spectral linewidth. If

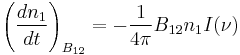

, emitting a photon with an energy E2 − E1 = hν. Due to the energy-time uncertainty principle, the transition actually produces photons within a narrow range of frequencies called the spectral linewidth. If  is the number density of atoms in state i then the change in the number density of atoms in state 1 per unit time due to spontaneous emission will be:

is the number density of atoms in state i then the change in the number density of atoms in state 1 per unit time due to spontaneous emission will be:

Stimulated emission

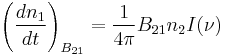

Stimulated emission (also known as induced emission) is the process by which an electron is induced to jump from a higher energy level to a lower one by the presence of electromagnetic radiation at (or near) the frequency of the transition. The process is described by the Einstein coefficient  (sr·m2·Hz·W−1·s−1 = sr·m2·J−1·s−1), which gives the probability per unit time per unit spectral radiance of the radiation field that an electron in state 2 with energy

(sr·m2·Hz·W−1·s−1 = sr·m2·J−1·s−1), which gives the probability per unit time per unit spectral radiance of the radiation field that an electron in state 2 with energy  will decay to state 1 with energy

will decay to state 1 with energy  , emitting a photon with an energy E2 − E1 = hν. The change in the number density of atoms in state 1 per unit time due to induced emission will be:

, emitting a photon with an energy E2 − E1 = hν. The change in the number density of atoms in state 1 per unit time due to induced emission will be:

where  denotes the spectral radiance of the isotropic radiation field at the frequency of the transition (see Planck's law).

denotes the spectral radiance of the isotropic radiation field at the frequency of the transition (see Planck's law).

Stimulated emission is one of the fundamental processes that led to the development of the laser. Laser radiation is, however, very far from the present case of isotropic radiation.

Photo absorption

Absorption is the process by which a photon is absorbed by the atom, causing an electron to jump from a lower energy level to a higher one. The process is described by the Einstein coefficient  (sr·m2·Hz·W−1·s−1 = sr·m2·J−1·s−1), which gives the probability per unit time per unit spectral radiance of the radiation field that an electron in state 1 with energy

(sr·m2·Hz·W−1·s−1 = sr·m2·J−1·s−1), which gives the probability per unit time per unit spectral radiance of the radiation field that an electron in state 1 with energy  will absorb a photon with an energy E2 − E1 = hν and jump to state 2 with energy

will absorb a photon with an energy E2 − E1 = hν and jump to state 2 with energy  . The change in the number density of atoms in state 1 per unit time due to absorption will be:

. The change in the number density of atoms in state 1 per unit time due to absorption will be:

Detailed balancing

The Einstein coefficients are fixed probabilities associated with each atom, and do not depend on the state of the gas of which the atoms are a part. Therefore, any relationship that we can derive between the coefficients at, say, thermodynamic equilibrium will be valid universally.

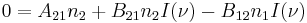

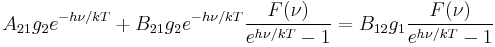

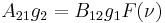

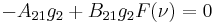

At thermodynamic equilibrium, we will have a simple balancing, in which the net change in the number of any excited atoms is zero, being balanced by loss and gain due to all processes. With respect to bound-bound transitions, we will have detailed balancing as well, which states that the net exchange between any two levels will be balanced. This is because the probabilities of transition cannot be affected by the presence or absence of other excited atoms. Detailed balance (valid only at equilibrium) requires that the change in time of the number of atoms in level 1 due to the above three processes be zero:

Along with detailed balancing, at temperature T we may use our knowledge of the equilibrium energy distribution of the atoms, as stated in the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution , and the equilibrium distribution of the photons, as stated in Planck's law of black body radiation to derive universal relationships between the Einstein coefficients.

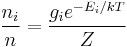

From the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution we have for the number of excited atomic species i:

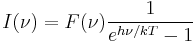

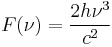

where n is the total number density of the atomic species, excited and unexcited, k is Boltzmann's constant, T is the temperature,  is the degeneracy (also called the multiplicity) of state i, and Z is the partition function. From Planck's law of black-body radiation at temperature T we have for the spectral radiance at frequency ν

is the degeneracy (also called the multiplicity) of state i, and Z is the partition function. From Planck's law of black-body radiation at temperature T we have for the spectral radiance at frequency ν

where:

where  is the speed of light and

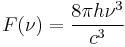

is the speed of light and  is Planck's constant. Note that in some treatments, the black-body spectral radiation energy density is used rather than the spectral radiance, in which case:

is Planck's constant. Note that in some treatments, the black-body spectral radiation energy density is used rather than the spectral radiance, in which case:

Substituting these expressions into the equation of detailed balancing and remembering that E2 − E1 = hν yields:

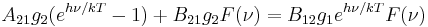

separating to:

The above equation must hold at any temperature, so

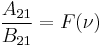

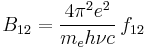

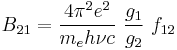

Therefore the three Einstein coefficients are interrelated by:

and

When this relation is inserted into the original equation, one can also find a relation between  and

and  , involving Planck's law.

, involving Planck's law.

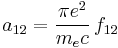

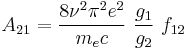

Oscillator strengths

The oscillator strength  is defined by the following relation to the cross section

is defined by the following relation to the cross section  for absorption:

for absorption:

where  is the electron charge and

is the electron charge and  is the electron mass. This allows all three Einstein coefficients to be expressed in terms of the single oscillator strength associated with the particular atomic spectral line:

is the electron mass. This allows all three Einstein coefficients to be expressed in terms of the single oscillator strength associated with the particular atomic spectral line:

See also

- Transition dipole moment

- Oscillator strength

- Breit–Wigner distribution

- Electronic configuration

- Fano resonance

- Siegbahn notation

- Atomic spectroscopy

- Molecular radiation, continuous spectra emitted by molecules

References

- ^ Bohr 1913

- ^ a b Einstein 1916

- ^ Sommerfeld 1923, p. 43

- ^ Heisenberg 1925, p. 108

- ^ Brillouin 1970, p. 31

- ^ Jammer 1989, pp. 113, 115

- ^ Weinstein, M.A. (1960). On the validity of Kirchhoff's law for a freely radiating body, American Journal of Physics, 28: 123-25.

- ^ Burkhard, D.G., Lochhead, J.V.S., Penchina, C.M. (1972). On the validity of Kirchhoff's law in a nonequilibrium environment, American Journal of Physics, 40: 1794-1798.

- ^ Baltes, H.P. (1976). On the validity of Kirchhoff's law of heat radiation for a body in a nonequilibrium environment, Chapter 1, pages 1-25 of Progress in Optics XIII, edited by E. Wolf, North-Holland, ISSN 00796638.

- ^ Milne, E.A. (1928). The effect of collisions on monochromatic radiative equilibrium, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 88: 493-502. [1]

- ^ Chandrasekhar, S. (1950). Radiative Transfer, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- ^ a b Mihalas, D., Weibel-Mihalas, B. (1984). Foundations of Radiation Hydrodynamics, Oxford University Press, New York, ISBN 0195034376.

- Einstein, A. (1916). "Strahlungs-Emission und-Absorption nach der Quantentheorie". Verhandlungen der Deutschen Physikalischen Gesellschaft 18, 318..

- Chandrasekhar, S. (1960). Radiative Transfer. Dover Publications, Inc. New York. ISBN 0-486-60590-6.

- Condon, E.U. and Shortley, G.H. (1964). The Theory of Atomic Spectra. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-09209-4.

- Rybicki, G.B. and Lightman, A.P. (1985). Radiative processes in Astrophysics. John Wiley & Sons, New York. ISBN 0-471-82759-2.

- Shu, F.H. (1991). The Physics of Astrophysics - Volume 1 - Radiation. University Science Books, Mill Valley, CA. ISBN 0-935702-64-4.

- Robert C. Hilborn (2002). "Einstein coefficients, cross sections, f values, dipole moments, and all that". physics/0202029. http://arxiv.org/abs/physics/0202029.

- Taylor, M.A. and Vilchez, J.M. (2009). "Tutorial: Exact solutions for the populations of the n-level ion". Pub. Astron. Soc. Pac. 121, 885: 1257–1266.

Bibliography

- Bohr, N. (1913). "On the constitution of atoms and molecules". Philosophical Magazine 26: 1–25. http://www.ffn.ub.es/luisnavarro/nuevo_maletin/Bohr_1913.pdf.

- Einstein, A. (1916). "Zur Quantentheorie der Strahlung". Mitteilungen der Physikalischen Gessellschaft Zürich 18: 47–62. and a nearly identical version Einstein, A. (1917). "Zur Quantentheorie der Strahlung". Physikalische Zeitschrift 18: 121–128. Bibcode 1917PhyZ...18..121E. Translated in ter Haar, D. (1967). The Old Quantum Theory. Pergamon. pp. 167–183. LCCN 66029628. See also [2].

- Brillouin, L. (1970). Relativity Reexamined. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0121349455.

- Heisenberg, W. (1925). "Über quantentheoretische Umdeutung kinematischer und mechanischer Beziehungen". Zeitschrift für Physik 33: 879–893. Translated as "Quantum-theoretical Re-interpretation of kinematic and mechanical relations" in van der Waerden, B.L. (1967). Sources of Quantum Mechanics. North-Holland Publishing. pp. 261–276.

- Jammer, M. (1989). The Conceptual Development of Quantum Mechanics (second ed.). Tomash Publishers American Institute of Physics. ISBN 0-88318-617-9.

- Sommerfeld, A. (1923). Atomic Structure and Spectral Lines. Brose, H. L. (transl.) (from 3rd German ed.). Methuen. http://books.google.com/books/about/Atomic_structure_and_spectral_lines.html?id=u1UmAAAAMAAJ.